If you ask me: what is the biblical evidence, if any, for the importance of interreligious dialogue? I would admit that it is impossible to find the term “interreligious dialogue” in the Bible because it is a modern terminology. However, the spirit of interreligious dialogue is able to find in several places in the Bible. This spirit marks the importance of how the Bible relates to the needs of non-Christians and how Gospel is proclaimed to the world.

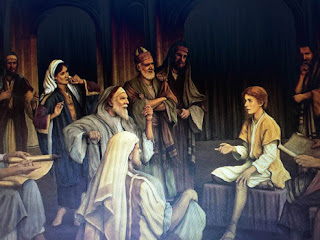

Luke 2, 41-53 talks

about Jesus’ visiting at the temple; the verse 46 is that, “Then, after

three days they found Him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the teachers,

both listening to them and asking them questions.” At the age of twelve, Jesus sat among the

teachers listening to them and asking questions of them. Even Jesus was just a young boy, he earned the

respect of the Jewish Teachers. Jesus’ discussion with the teachers really

shows a so-called spirit of dialogue. Moreover, Jesus raised religious topics to the

Jewish teachers, and they were amazed by his understanding and his answers. The

important point is that Jesus and those teachers created an atmosphere of conversation with respect

and listening to one another. In this context, Luke also wanted to make known Jesus to others. He brought them along to understand more about Jesus. In this sense,

the proclamation of the Good News might be emerged in an “early interreligious

dialogue”.

Luke 2, 41-53 talks

about Jesus’ visiting at the temple; the verse 46 is that, “Then, after

three days they found Him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the teachers,

both listening to them and asking them questions.” At the age of twelve, Jesus sat among the

teachers listening to them and asking questions of them. Even Jesus was just a young boy, he earned the

respect of the Jewish Teachers. Jesus’ discussion with the teachers really

shows a so-called spirit of dialogue. Moreover, Jesus raised religious topics to the

Jewish teachers, and they were amazed by his understanding and his answers. The

important point is that Jesus and those teachers created an atmosphere of conversation with respect

and listening to one another. In this context, Luke also wanted to make known Jesus to others. He brought them along to understand more about Jesus. In this sense,

the proclamation of the Good News might be emerged in an “early interreligious

dialogue”.

In

the Acts of the Apostles 17: 17-23, (Paul

at Athens), Paul met many different people at the synagogue. Although they were not in the same

community with him, he still engaged in a conversation with them. “So he was reasoning in the synagogue with

the Jews and the God-fearing Gentiles and in the market place every day with

those who happened to be present. And

also some of the Epicurean and Stoic philosophers were conversing with him.” He was humble himself to observe and learn their

different religious practices. He did

not intend to preach to them, but to be with them first. He tried to have a direct

communication and interaction with those religious practitioners

to understand their ways of worship deeply. From his observation and experience, he looked

for the suitable way to communicate the Gospel according to

their own traditions. This is quite clearly in verse 23, "For while I was passing through and

examining the objects of your worship, I also found an altar with this inscription,

'TO AN UNKNOWN GOD' therefore what you worship in ignorance, this I proclaim

to you.” This verse shows that

Paul’s spirit of interreligious dialogue was very clear. It was a change that Paul came to be with those non-Christians, to understand, and walk with them.

The encounters above could be one of the motivations that the Church has found herself on Interreligious Dialogue as an important mission. Clearly, specific contributions that texts such

as Nostra Aetate and Dialogue and Proclamation have made a great effort to a Catholic theology of

interreligious dialogue. Perhaps, the greatest contribution of Nostra Aetate is the Church’s recognition of her

relationship to other religions, especially a new spirit of her relationship to

Judaism. This contribution is considered as an opportunity to heal the wounded

memories between Jews and Christians. The idea is not only meant in relationship with

Judaism, but also touches all the religions as positive contributions to global

solidarity and religious harmony. We can see that the

dialogical spirit of Nostra Aetate is clear in its opening words, “In

her task of promoting unity and love among men, indeed among nations, she

considers above all in this declaration what men have in common and what draws

them to fellowship. (1)” This emphasizes on a

new understanding of the Christian-Jewish relation which encourages a mutual

respect, unity, and friendship. An author

reflects on Nostra Aetate, saying that, "For

nearly 40 years, Nostra Aetate has promoted a rich dialogue between

Christians and Jews to encourage mutual understanding and respect for each

other's faith and religious convictions."

The encounters above could be one of the motivations that the Church has found herself on Interreligious Dialogue as an important mission. Clearly, specific contributions that texts such

as Nostra Aetate and Dialogue and Proclamation have made a great effort to a Catholic theology of

interreligious dialogue. Perhaps, the greatest contribution of Nostra Aetate is the Church’s recognition of her

relationship to other religions, especially a new spirit of her relationship to

Judaism. This contribution is considered as an opportunity to heal the wounded

memories between Jews and Christians. The idea is not only meant in relationship with

Judaism, but also touches all the religions as positive contributions to global

solidarity and religious harmony. We can see that the

dialogical spirit of Nostra Aetate is clear in its opening words, “In

her task of promoting unity and love among men, indeed among nations, she

considers above all in this declaration what men have in common and what draws

them to fellowship. (1)” This emphasizes on a

new understanding of the Christian-Jewish relation which encourages a mutual

respect, unity, and friendship. An author

reflects on Nostra Aetate, saying that, "For

nearly 40 years, Nostra Aetate has promoted a rich dialogue between

Christians and Jews to encourage mutual understanding and respect for each

other's faith and religious convictions."

In the same spirit,

“Dialogue and Proclamation” (1991) continues to contribute a deep sense of

interreligious dialogue, not just stopping at understanding and respect for each

other’s faith, but sharing the noble values of each other’s

traditions. In this engaging dialogue, participants are called to

listen to different spiritual and religious values and explore to the richness of

each religious tradition. In this way, Christians can deepen other

religious traditions, and the Gospels may be proclaimed to other believers as well. This spirit of “Dialogue and Proclamation” is made concrete in No 40, “It

reaches a much deeper level, that of the spirit, where exchange and sharing

consist in a mutual witness to one's beliefs and a common exploration of one's

respective religious convictions. In dialogue, Christians and others are

invited to deepen their religious commitment, to respond with increasing

sincerity to God's”.